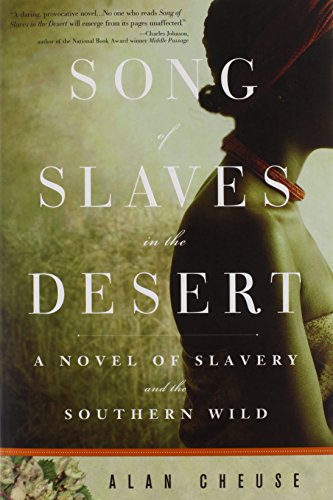

Items related to Song of Slaves in the Desert

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

A single bright star glowed steadily like a stone fixed in the firmament of ocean blue sky above the red mosque, years and years back, when her grandparents were children. Their children? The jar-maker and his wife, he was the potter, she the weaver who made the cloth that held the jars with the distinctive design-three horizontal lines, one vertical-and supplied the household wares to the sheik who paid for the mosque. The father of the jar-maker had put him out to service with the sheik in exchange for the guarantee of an annual supply of grain for the family. In the seventh year of his service, when his father had died and the grain had rotted, the young artisan met the woman who would become his wife-because he noticed the cloth she had woven hanging in the market and imagined his jars wrapped in her weaving-a sign of lightning, a splash of rain, a distinctive design.

This turned out to be either a very good thing or a very bad thing. Her father would not give her up without a large payment, and the young jar-maker had to pledge another ten years to the sheik in order to buy this woman as his wife. As the story went, after the sheik, or, to be specific, his bookkeeper, agreed, the young jar-maker walked away, out to the edge of the town, where the river turned south-it flowed east from near the coast before bending around the city in its southerly way-and looked up into the clear sky and saw a river stork pinned by the light against the pale blue screen of air. He allowed his mind to soar up with the bird, wondering what the future might be like, and if he would ever become a free man, when in the distance the muezzin sang the call to prayer. The potter returned to the town having decided that he would give up one thing in his life, in this case, ten more years, in order to obtain another. In a crowd of men dark-haired and white, he bent far forward and touched his forehead to the cool tiles of the floor, breathing in breath and sweat, sweet-wretched body-gas and tantalizing anise, and when he drew himself upright again he saw in his mind the weaver, the years ahead, and he knew that he had chosen the right path.

Who knows how to tell of the passing of ten years in happiness and some struggle in just a few words, so that the listener has a sense of how quickly time passes and yet still captures the bittersweet density of all that time together? Bodies entangled at night, hands working together at their craft, cooking, washing, bathing, cleaning, praying, and now and then stealing the time to wander along the river and do nothing but watch for the rising of that same stork he had seen on that day that now seemed so long past. The weaver gave birth to their first child, a boy. And then another, a girl. And then, another girl.

(And oh, my dear, she said, try to tell you this about birth and you discover how far short of real life words fall, and yet how else to make any of these events known? Words! Words, words, words! The weight, the aches, the fears, the stirring, the shifting bleeding tearing pain and struggle!

And the cries of mother, and child! But what do we have but memories, and these translated into words?)

And then there arose a situation on which everything else turned. It had been the custom, as you may already have wondered about, that artisans such as the jar-maker and weaver might live outside the sheik's compound, even as in other cities the situation might be the reverse. The jar-maker found this to be a good arrangement. It gave him all of the seeming liberty of a free man, at least in that he could move about the city, and when it came time to deliver his goods to the sheik's compound he faced the bookkeeper almost as though he were an equal.

"Six large water jars," he said one morning in the cool season when the river in the distance had become carpeted with migrating birds.

"Six large water jars," the bookkeeper took notice. He recorded the transaction and with a wave of his stylus seemed ready to dismiss the jar-maker.

So it had gone with every delivery of every variety of container the jar-maker had created for his master, many times a year for a long number of years. Six water jars? Six water jars. Twenty cups? Twenty cups. Ten bowls? Ten bowls. He created them and delivered them. And dishes-yes, now and then the jar-maker turned dish-maker, using what he regarded as his wife's family design-three lines horizontal, one vertical-for the plates from which the sheik and his guests would eat. Today, as was more often than not the case, it was diminutive jars. People drank from them often, which meant some got broken, always. Jars. The bookkeeper counted. And raised his hand to dismiss him.

Year in, year out.

All in the name of God.

The artisan in his soul felt as though his supposedly temporary arrangement with the sheik would last forever. His family was growing. And still he found himself, as if in a dream of continuous repetition sometimes talked about by street-shop philosophers in the town, arriving at the compound, ordering the assistant, a blue-black slave from the South given to him by the sheik, to carry the pottery, standing before the bookkeeper, and waiting to be dismissed.

A free life seems so simple, filled with small pleasures! All he desired in those moments was the right to turn and walk away without having to wait for the signal that he was dismissed. As discourteous as that would have been, he contemplated the delicious possibility of it.

But did that moment ever arrive?

Here in the shade of the courtyard, cool shadows drifting down on them and sheltering them from the direct rays of the sun and buffering the heat reflected off the red walls of the main house, he enjoyed feeling liberated within the confines of his indentured state, so that, it seemed to him in his momentary fantasy, if he stood still the moment would never pass and he could live within it, even push against its limits and enlarge them, until old age overtook him and he withered and died free.

A man never knew how free he might be until he became a captive, for a decade or a lifetime, and a free man never knew just how enslaved he was until he found himself behaving as though invisible ropes tethered him to a routine of years and months and days. And so the artisan stood there, deeply immersed in the moment, poised to turn at the lowering of the bookkeeper's hand, fretting about the freedom he might never possess.

The bookkeeper cleared his throat, and the jar-maker shifted in his space, already turning.

"Before you go..." the sheik's man said. "There is something..."

The jar-maker froze in place, fixed like one of the designs on his pots when the heat rose high enough to fix it forever. Freezing, heating-oh, he knew, he felt it in his blood, he was somehow done, done for this world.

The bookkeeper again cleared his throat in such a formal way that the jar-maker believed in that instant that he might be about to announce the sheik's pleasure over the special designs.

"I should not be telling you this."

"Yes, sir?"

The jar-maker, a man old enough so that if he were free others would address him with similar respect, gave the bookkeeper his best attention.

"You must pack your bags. You and your family must pack your bags."

The jar-maker felt the chill and thrill of surprise running in his veins.

"Why do you say this, sir?"

The bookkeeper narrowed his eyes and leaned ever so slightly closer to the jar-maker.

"I should not be saying this at all. But-"

Again, a world in an instant! We're free! the jar-maker told himself, free before our time! The sheik in his wisdom-

"My master-"

"Yes, sir?" The jar-maker interrupted, and then cursed himself for interrupting.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSourcebooks Landmark

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 1402267037

- ISBN 13 9781402267031

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages528

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Song of Slaves in the Desert

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00ZVSA_ns